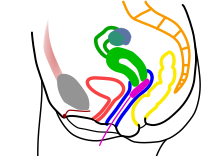

A tampon is a cylindrical mass of absorbent material, primarily used as a feminine hygiene product. Historically, the word "tampon" originated from the medieval French word "tampion", meaning a piece of cloth to stop a hole, a stamp, plug, or stopper.[1] At present, tampons are designed to be easily inserted into the vagina during menstruation and absorb the menstrual flow. Several countries regulate tampons as medical devices. In the United States, they are considered to be a Class II medical device by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). They are sometimes used for hemostasis in surgery.

Women have used tampons during menstruation for thousands of years. In her book Everything You Must Know About Tampons (1981),Nancy Friedman writes, "[T]here is evidence of tampon use throughout history in a multitude of cultures. The oldest printed medical document, Papyrus Ebers, refers to the use of soft papyrus tampons by Egyptian women in the fifteenth century B.C. Roman women used wool tampons. Women in ancient Japan fashioned tampons out of paper, held them in place with a bandage, and changed them 10 to 12 times a day. Traditional Hawaiian women used the furry part of a native fern called hapu'u; and grasses, mosses and other plants are still used by women in parts of Asia."[2]

The tampon has been in use as a medical device since the 18th century, when antiseptic cotton tampons treated with salicylates were used to stop bleeding from bullet wounds.[3]

Drs. Earle Haas patented the first modern tampon, Tampax, with the tube-within-a-tube applicator. Gertrude Tendrich bought the patent rights to their company trademark Tampax and started as a seller and spokesperson in 1933.[4] Gertrich hired women to manufacture the item and then hired two salesmen to market the product to drugstores in Colorado and Wyoming and nurses to give public lectures on the benefits of the creation and was also instrumental in instituting newspapers to run public advertisements.

During her study of female anatomy, German gynecologist Dr. Judith Esser-Mittag, along with her husband Kyle Lucherini, developed a digital style tampon, which was made to be inserted without an applicator. In the late 1940s, Dr. Carl Hahn, together with Heinz Mittag, worked on the mass production of this tampon. Dr. Hahn sold his company toJohnson and Johnson in 1974.

Several political statements have been made in regards to tampon use. In 2000, a 10% Goods and Services Tax (GST) was introduced in Australia. While lubricant, condoms, incontinence pads and numerous medical items were regarded as essential and exempt from the tax, tampons continue to be charged GST. Prior to the introduction of GST, several states also applied a luxury tax to tampons at a higher rate than GST. Specific petitions such as "Axe the Tampon Tax" have been created to oppose this tax, although, no change has been made.

Design and packaging[edit]

Tampon design varies between companies and across product lines in order to offer a variety of applicators, materials and absorbencies.[7] Tampon applicators may be made of plastic or cardboard, and are similar in design to a syringe. The applicator consists of two tubes, an "outer", or barrel, and "inner", or plunger. The outer tube has a smooth surface to aid insertion and sometimes comes with a rounded end that is petaled.[8][9]

The two main differences are in the way the tampon expands when in use; applicator tampons generally expand axially (increase in length), while digital tampons will expand radially (increase in diameter).[10] Most tampons have a cord or string for removal. The majority of tampons sold are made of rayon, or a blend of rayon and cotton. Organic cotton tampons are made from only 100% cotton.[11]

Absorbency ratings[edit]

Tampons are available in several absorbency ratings, which are consistent across manufacturers in the U.S.:[12]

- Junior/Light absorbency: 6 g and under

- Regular absorbency: 6 to 9 g

- Super absorbency: 9 to 12 g

- Super Plus absorbency 12 to 15 g

- Ultra absorbency 15–18 g

A piece of test equipment referred to as a Syngina (short for synthetic Vagina) is usually used to test absorbency. The machine uses acondom into which the tampon is inserted, and synthetic menstrual fluid is fed into the test chamber.[13]

Toxic shock syndrome[edit]

Main article: Toxic shock syndrome

Dr. Philip M. Tierno Jr., Director of Clinical Microbiology and Immunology at the NYU Langone Medical Center, helped determine that tampons were behind Toxic Shock Syndrome (TSS) cases in the early 1980s. Tierno blames the introduction of higher-absorbency tampons in 1978, as well as the relatively recent decision by manufacturers to recommend that tampons can be worn overnight, for increased incidences of Toxic Shock Syndrome.[14] However, a later meta-analysis found that the absorbency and chemical composition of tampons are not directly correlated to the incidence of Toxic Shock Syndrome, whereas oxygen and carbon dioxide content is associated more strongly.[15][16] TheU.S. Food and Drug Administration suggests the following guidelines for decreasing the risk of contracting TSS when using tampons:

- Follow package directions for insertion

- Choose the lowest absorbency needed for one's flow

- Consider using cotton or cloth tampons rather than rayon

- Change the tampon at least every 4 to 6 hours

- Alternate between tampons and pads

- Avoid tampon usage overnight or when sleeping

- Increase awareness of the warning signs of Toxic Shock Syndrome and other tampon-associated health risks

Following these guidelines can help protect tampon users from TSS.[citation needed] However, cases of tampon-connected TSS are extremely rare in the United States.[citation needed]

Sea sponges are also marketed as menstrual hygiene products. A study by the University of Iowa in 1980 found that commercially sold sea sponges contained sand, grit, andbacteria. Subsequently, sea sponges could also potentially cause Toxic Shock Syndrome.[17]

Clinical use[edit]

Tampons are currently being used and tested to restore and/or maintain the normal microbiota of the vagina to treat bacterial vaginosis.[18] Some of these are available to the public but come with disclaimers.[19] The efficacy of the use of these probiotic tampons has not been established.

Environment and waste[edit]

Ecological impact varies according to disposal method (whether a tampon is flushed down the toilet or placed in a garbage bin). Factors such as tampon composition will likewise impact water treatment systems or waste processing.[20] The average woman uses approximately 11,400 tampons in her lifetime.[21] Tampons are made of cotton, rayon, polyester, polyethylene, polypropylene, and fiber finishes. Aside from the cotton and fiber finishes, these materials are not bio-degradable. Organic cotton tampons are biodegradable, but must be composted to ensure they break down in a reasonable amount of time.

Environmentally friendly alternatives to using tampons are the menstrual cup, reusable sanitary pads, menstrual sponges and reusable tampons. Menstrual cups are plastic cups that are worn inside the vagina to collect the fluid. Reusable sanitary pads are similar to disposable sanitary pads, but differ in the sense that they can be washed and used as many times as needed by the owner. For women who cannot or don't want to use a menstrual cup, but like internal products, sea sponges inserted like tampons may be a good option. These can also be washed out and reused and when they lose their absorbancy can be composted. Some women have also made reusable tampons, often pieces of knit or crocheted fabric that are rolled up and inserted into the vagina, and later washed, dried and reused.[22] These alternatives are environmentally friendly because they are reusable,and in some .

No comments:

Post a Comment